I was only nine years old at the time, but I can vividly remember my father coming home with the sad news. Like so many times before — and too many times after — the sea had once again taken its deadly toll on our community.

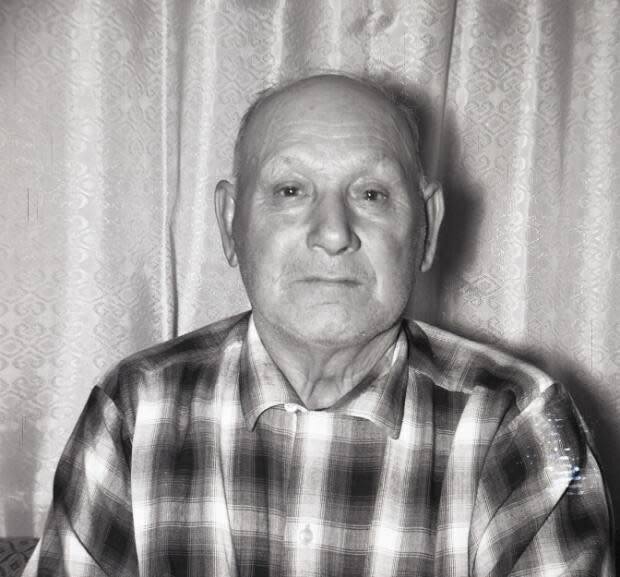

Two of the seven-man crew of the Administratrix were saved. In 1967 I interviewed George Barnes, one of the survivors.

The 120-ton vessel — low in the water and built for speed — was at one time used for rum-running. It left St. John’s on a Thursday morning, April 29, loaded on deck and below with gasoline and oil in 45-gallon drums, bound for her home port of Grand Bank. Shortly after leaving she encountered heavy fog.

Around 6 p.m. the ship was steaming along when the men on watch heard a whistle. They weren’t sure if it was the foghorn on Cape Race or a boat.

“Out of the thick fog, less than 100 yards away, loomed the large, 7,500-ton Norwegian steamer Lovdal.… She was coming right at us at a speed of nine knots. We couldn’t avoid her — she smashed right into our little freighter and knifed right through the engine room.”

The Administratrix was cut in half.

“I was at the wheel, with the skipper, captain Forsey, standing beside me. Seaman Robert Lee was also in the wheelhouse. The front section of our boat tipped up and slowly sank, and the stern section did likewise,” said Barnes.

“Within three minutes from the time of impact I was in the water. It was freezing and fuel oil caked my face and got into my eyes. I didn’t know how to swim a stroke, but I guess the air in my oilskins kept me afloat until I saw a section of the pilot-house floating towards me. I grabbed it and hung on.”

Oil barrels were colliding all around them, said Barnes.

“I think the captain must have been knocked unconscious shortly after he went overboard. I heard the cook, Charlie Fizzard, calling out to me, calling my name, but because of the thick fog I couldn’t see him,” he said.

“After about half an hour hanging onto the wreckage of the pilothouse, a lifeboat from the Norwegian steamer picked me up. We then found and picked up the cook. The search continued for some hours but there was no sign of the other five members of our crew, including the captain.”

The two survivors said they were treated the very best by the crew of the Lovdal, “given dry clothing and hot drinks and made comfortable in every possible way” George Barnes told a local newspaper.

The men who were lost included captain Chesley Forsey, chief engineer George Sam Welsh, second engineer Archibald Rose and sailors Harvey Keating and Robert Lee.

The two survivors, who suffered only minor injuries, were the cook, Charles Fizzard, and the first mate, George Barnes.

All members of the crew were married, and some of them left large families. The tragedy, like many before and after, cast a gloom over our town. Flags flew at half-mast in Grand Bank that Saturday, as the entire community shared the sorrow and grief.

According to a document I have in my possession, a claim was made against the Lovdal, and each family of the deceased men received between $8,000 and $10,000. It appears that at least one of the families received such compensation, but I was unable to verify with the descendants of other who lost their lives that was the case.

It is believed that the 45-year-old chief engineer, George Sam Welsh, was killed when the large Norwegian freighter knifed through the engine room. He was the father of nine children, six of them still living at home.

One of the youngest children, William — Bill — told me that when his mother would come home after working on the beach all day, she would be so tired that to help her go to sleep, she would “visualize walking up every street, counting all the widows in Grand Bank.” The town’s history has documented that up to 300 seamen were lost sailing out of that port during the banking schooner and trawler eras.

An older daughter, Selena — working in St. John’s at the time and getting married in the Wesley United Church — was the last of the family to talk to their dad before his vessel left for Grand Bank. She went down on the wharf to tell her dad about her upcoming wedding.

Doreen Williams, daughter and only child of seaman Harvey Keating, was only five years old when her dad was lost. As far as she knows, she told me, her mother didn’t receive any compensation, maybe because her mother was working teaching school, even though the most pay her mother ever received teaching was $102 monthly.

The Keatings, like most of the other families, first heard about the tragedy on the radio.

“I heard the announcer say something about ‘two boats had bumped together,'” she said. “Shortly after we looked out the window and saw [Salvation Army clergyman] Maj. Rideout coming — when my mom saw him she knew the news was very grim. For many years, into my teens, I kept looking for my dad, hoping that someday he’d come back and we would be together again.”

According to James Welsh this is the only thing he is aware of regarding compensation to his mother.

Welsh told me his mom also worked on the beach for awhile and saved enough money to buy herself her first pair of eyeglasses but the most memories of his mom working was of her taking in sewing and knitting for other people.

“The sewing machine in the kitchen would be humming continuously,” he said.

*****

Credit belongs to : ca.news.yahoo.com

Atin Ito First Filipino Community Newspaper in Ontario

Atin Ito First Filipino Community Newspaper in Ontario